The Skilled Observer

in Art & Science

The Skilled Observer courses: Why Now?

Photo by Paul Solomon

It is a challenging time to be a student or a teacher. Education is belittled, knowledge is ridiculed, and science is distrusted. Specialization is failing students. Curiosity and creativity are stifled in silos of traditional academia and in the hierarchical confines of medicine. Deciphering the causes of disease, climate collapse and other urgent problems, depend upon the ability to work collaboratively in cross-disciplinary territory.

To address these challenges, I created a new course of study in 2015, called The Skilled Observer in Art and Science. It demonstrates how artists, scientists, and medical providers use intuition, embodied cognition, and pattern recognition to tease from threads of data, the connective tissue that makes systems work.

The Skilled Observer in Art and Science was designed to function beautifully as an asynchronous, synchronous, or hybrid class. It can be customized to fit the needs of diverse audiences.

Two examples: The Skilled Observer course is in use as a 2000-level course for undergraduates at Western Michigan University. Another version of the course is offered as an elective for 4th-year medical students at Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine.

Among the online modules are the Languages of Art and Science; Religion, Art, and Science; In the Mind’s Eye: The Neuroscience of Vision; The Neuroscience of Music; and The Skilled Observer in Art and Medicine. Other modules address global warming, architecture, geoscience, mathematics, and physics seen through the eyes and ears of artists, clinicians, and scientists.

Inset: View of the Moon, daguerreotype by John A. Whipple, February 26, 1852, at Harvard College Observatory, Cambridge, MA

Background: Detail of photograph by NASA astronaut Bill Anders, from the Apollo 8 spacecraft, on December 24, 1968

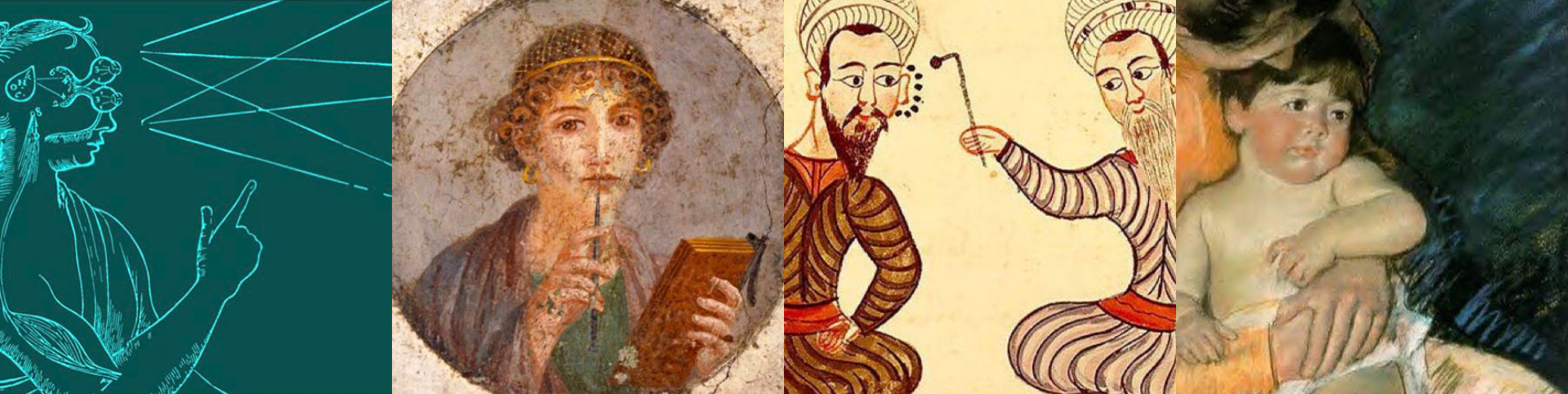

L – R: Illustration from Treatise on Man, by Rene Descartes, 1686; Pompeian woman with wax tablet, ca. 50 CE; Illustration from 15th century medical treatise; Mother and Child, Mary Cassatt, 1893

Meet Some Skilled Observers

“Seeing and touching the rocks is necessary for full understanding.”

7 Minutes with Heather Petcovic

Geoscientist and Professor of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Heather Petcovic researches geological cognition, geologic mapping, spatial ability, and patterns of movement impact problem-solving. She documents student conceptions of complex biogeochemical systems in field-based research.

“Humans are exceptionally good at finding patterns and finding individual pieces of information and a whole big mess of mess of data,” says Petcovic, “(but) seeing and touching the rocks is necessary for full understanding.”

“Our science works the same way as other sciences do. We have ideas, we test those ideas by forming hypotheses and conclusions, we test them against theories and what others have said, but the fundamental distinction of geosciences is that our knowledge comes from the natural world.”

We talked along a stream in the Asylum Lake Preserve, in Kalamazoo, MI.

“Tools That Link Mathematics to Art”

7 Minutes with Emily Lynch Victory

Emily Lynch Victory is a painter, mathematician, and educator, with degrees in math and in fine-art. “I am a very busy ‘doer’ type, unless I am doing artwork.” says Victory. “If I sit and paint 8,000 black rectangles, it is calming. The process is meditative. I like to sit there and just explore patterns. . . . taking the time and doing every line, and calculating.” Based in Minnesota, Victory has a studio practice as an artist and teaches mathematics. Victory says,

“If you lined up a mathematician’s career, you would see the sequence of problem solving that leads to a greater understanding in both subjects. There are tools that link mathematics to art, and as long as you have those tools, it will help you as an artist.”

Emily and I talked while she was installing her paintings at the 8th Annual ArtPrize competition in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

“It’s all made up, it’s all in your head.”

5 minutes with John Jellies

Neurobiologist, and Professor of Biological Sciences at Western Michigan University, John Jellies uses behavioral, biochemical, cellular and electrophysiological techniques to ask a variety of questions. Jellies does research about vision, using leeches. He is also an artist.

“I teach human physiology, Jellies says. “I tell stories because we are so anthropocentric, we are most interested in what it means to be human. It’s important to be able to define what the hell is not human?”

“How do we know from within our own experience what non-human is, if everything we see, hear, taste, and feel is only within our own little brain?” asks Jellies. “We are such visual creatures . . (but) our ability to perceive anything has almost nothing to do with the energy that you’re perceiving – It’s all made up, it’s all in your head. You (also) depend upon somatosensation, your body position, your sense of time. The way your visual system is moving through time is influenced profoundly by your other senses.”

We talked in his lab while his leeches looked on.